All the Places We Called Home

Photo: Sigrid Marianne Gayangos

Zamboanga City | 3,384 words

Morning Breeze Subdivision, Tugbungan

When Luciano first came to the swampy Barangay Tugbungan, fish processing warehouses had yet to dot the muddy, buggy area that sits right next to the lush wetlands. But he knew that the waters surrounding that part of Zamboanga City had a profusion of marine life, thanks to the nearby presence of mangrove forests. He also knew he could take the skills passed down in his family and build a new life there. They had traveled to several other regions before coming to the east coast of Zamboanga—some five kilometers from the bustling center of the port city—drifting from one coastal area to another, at times leaving themselves at the mercy of sheer luck facing the vagaries of nature. This time, however, it was as though they were guided by ancient waves that carried them to that shore.

In 1977, Luciano’s family compound finally established itself in Morning Breeze Subdivision. Despite its name, the early hours there were not permeated with the freshness of morning dew, as one would imagine. There was no hint of floral sweetness or the pleasantly sharp scent of grass, either. Instead, the air remained heavy with the pungent stench of salt and fish guts. Freshly-caught fish do not emit unpleasant fishy odors: in fact, the smell should be no different from the sweet aroma of the ocean. It was the bularan, or fish drying warehouse, in the middle of the family compound that was responsible for producing such odors.

Once the boats had returned from fishing, compradors awaited on shore to buy the catch of the day directly from the fisherfolks. They would then distribute these to various flea markets in the city at a higher price. A massive chunk of the fisherfolks’ catch would be gone in mere minutes, and what remained would eventually be sent to the bularan for further processing. It started with meticulous gutting—slitting the fish at the dorsal side and removing gills, milt, and viscera—followed by washing and then soaking in a salt solution. These tasks were carried out in the birukan, where the brining stations were. After which, the fish were laid on kaping mats to be dried-out on rows of bamboo slats. It is through these steps of the fish drying process that microbial decomposition occurs which causes the fish to emit the briny tang that lingers in your nostrils.

To Luciano and his wife Maria, however, the scent meant there was money for the family and food on the table. It was the sweetest smell for them—morning breeze indeed. It was the smell that allowed them to build their home, and the homes of their children, surrounding the bularan. In the middle of the bularan stood the kamalig, where the dried fish, or bulad, were stored before distribution. It was the very first structure erected in the family compound: its walls were made from repurposed wooden fish crates, while its roof had a layer of galvanized iron sheets and pitched nipa leaves. Concealed within the wooden columns of the kamalig were seahorse bones, which Luciano believed fortified both the foundation of the edifice and the ties binding his family. Luciano was right about many things. This was not one of them.

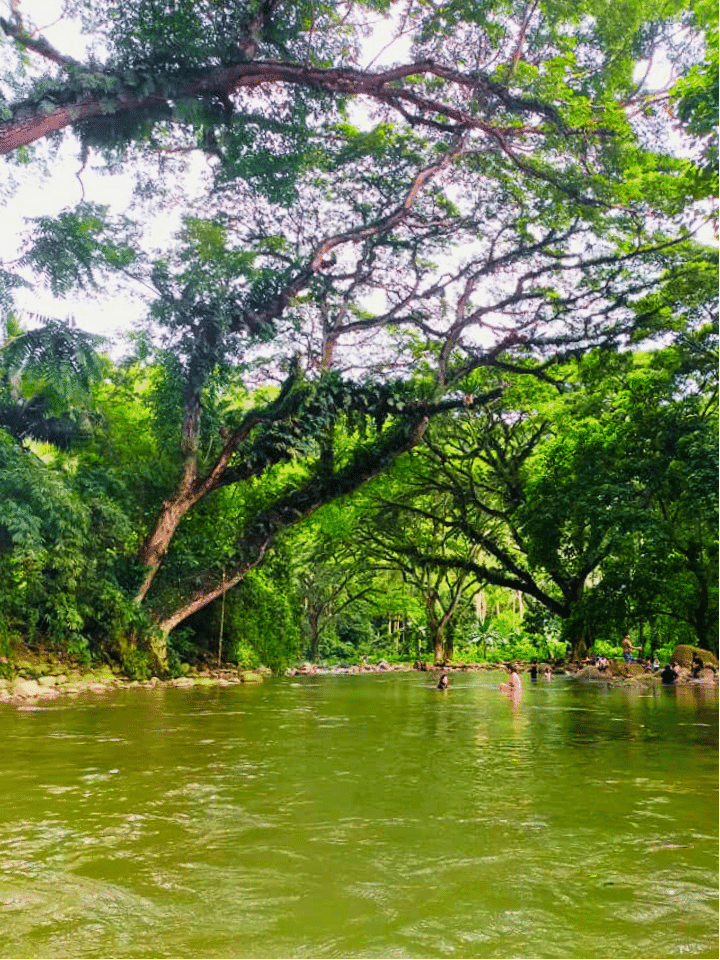

Villa Hermosa Subdivision, Pasonanca

Sometimes I still find myself wondering if it was all real or merely an extended, vivid dream: the sun-kissed days, the blooming wildflowers, the tree-lined lanes and open meadows. We went up the hills of Pasonanca where it smelled oddly of pine trees. “There it is! That’s it!” Papa pointed at the raging river that coursed through the barangay, its curving form disappearing here and there amidst the hillside houses. The watershed in upper Pasonanca cradles the headwaters of the Tumaga River, and Papa told us tales of his boyhood there, swimming against the currents just to collect logs and driftwood so they had something to burn for heat and light at home. How different from the life Mama had in her family compound, treated like a little princess with several ladies-in-waiting attending to her every need.

Together, Mama and Papa built a home that smelled like there was always something cooking in the kitchen. Some days, the buttery embrace of freshly-baked cookies and pastries wrapped its arms around our little home; other times, the air carried the savory notes of meat broth that had been simmering for hours. And, sometimes, the smell of bulad still lingered in the air from the care packages our grandparents sent. Mama, being the youngest daughter, still had a designated lot for her back in the family compound. She and Papa, however, had decided it was best to raise us in an environment where they had more privacy and parental autonomy. It was no easy task. My first few months in this world were spent in a cramped apartment near Papa’s workplace, while our hillside home was still taking shape. It was a small two-floor house in Villa Hermosa Subdivision, a low-cost government housing project. But with each nail hammered and each wall painted, the house turned into a sanctuary of possibilities for our family.

It took some convincing as well for my grandparents to accept my parents’ decision to live outside the family compound. Mama’s designated lot was right next to my grandparents’ house. When Luciano first visited our home in Pasonanca, he had to park his car several blocks away since it wouldn’t fit in the narrow path that led to our home. He looked around and said it felt like he was in a matchbox. Such was his humor and, really, it was just an old man’s last attempt at convincing his youngest and dearest daughter to live near them instead. Seeing that the young couple had made up their minds, he was quick to add that it was not unlike his first “matchbox home” in Cotabato when his family was also just starting out and where he had the fondest of memories.

My sister and I were born two years apart and we grew up playing with the neighborhood kids who were around our age. We swam in the rivers of Pasonanca, climbed trees during endless rounds of hide and seek (except for that one sampaloc tree inhabited by a vengeful ghost), and trekked Mount Pulong Bato to reach the Station of the Cross on many Easters. We had our first taste of algebraic explorations while ascending the hills of Pasonanca, where Papa engaged us in a game of “Guess that Number”; we recited our first attempts at poetry to the rustling leaves in the park. In 1999 our little brother joined the picture and he, too, enjoyed the same happy childhood in the idyllic little town. Everything was perfect. Until, of course, it wasn’t.

With my grandfather’s passing, my grandmother’s once-vibrant health yielded to a steady decline. A few years later, in 2001, members of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) abducted scores of civilians and used them as human shields against government forces. We escaped by a hair’s breadth—all thanks to our vigilant Muslim neighbor who frantically knocked on our gate at four in the morning, giving us just enough time to hastily pack up essentials and leave our home. There were over a hundred civilian captives from barangays Santa Maria and Pasonanca. We were part of the lucky few who managed to flee and seek shelter elsewhere. What was once a safe haven for us was now imbued with an unsettling sense of fear. The standoff lasted for only a few days, but it spelled years of subsequent political unrest in the city.

Morning Breeze Subdivision, Tugbungan 2

Two years after the MNLF siege and as my grandmother bore the brunt of a second stroke, a pivotal decision was made by my parents: we were to leave our home in Pasonanca and stay with our grandmother to care for her. The passing of my grandfather marked not only the end of an era but the crumbling of a legacy. The once-thriving family enterprise, which he had so deftly navigated, was now but a husk of its former self. Luciano was so proud of what he had built for himself in Zamboanga, but he died asking how much money he owed other people. While we were living our carefree and simple life in Pasonanca, some of my mother’s siblings were apparently driven by the desire to outdo one another by living lavishly and building increasingly extravagant residences within the family compound—all at the expense of the family business, which eventually drained my grandparents’ hard-earned money.

They lost all their ships, trucks, and fish ponds. No one knew how to manage the financial resources, only how to spend them. It couldn’t be denied, however, that the location of the kamalig remained ideal. And so it found a new vocation: it became a warehouse rented out to new players in the fish drying business of Zamboanga City. Of course, the revenue was far from what it had once provided, but the monthly rent became a modest influx of sustenance for my widowed grandmother. It was her lifeline, with its proceeds directly channeled toward her medical and care costs.

My parents did not sell our house in Pasonanca though. In their mind, as soon as my grandmother was nursed back to health and they found a more capable carer to stay with her, we would all return to our childhood home. But none of the other relatives already residing in the compound were eager to take on the task. Mama’s lot remained empty—no, in fact, it wasn’t empty when we got there. It had turned into a dumpsite. We couldn’t fathom the level of neglect the family compound had suffered, and it was just futile to point fingers. Perhaps it was mercy at that point that Luciano did not live to see the state of the place.

Every corner of the family compound bore the weight of years of abandonment: the kamalig’s roofs were sagging, doors and gates were sighing for repair, and pathways were overgrown. Stagnant pools of murky water were scattered in the dumpsite. We were not even done unpacking and nesting in the new place yet when our parents set on the almost impossible task of clearing the compound up. I remember an entire summer devoted to giving our grandparent’s house a fresh coat of paint, sharing the tasks among ourselves for it was beyond my father’s salary to employ maintenance for a house that big. Not long after, with the help of some kids who grew up around the bularan—and with my father’s incredible talent in gardening—what had been a desolate dumpsite now turned into a blossoming kitchen garden. Fruit trees, branches bowing heavily with ripening offerings, stood among arrays of vegetables and herbs. Birds flitted among the branches, a playful goat named Dao Ming Si roamed the expanse, and ducks glided gracefully across the small pond.

It was through that project that our family coped with leaving our hillside home. In the new kitchen garden we had a realm of vibrant colors and intoxicating fragrances, not unlike the forest parks we frequented in Pasonanca. The air was thick with the mingling scents of a myriad of flowers and succulent fruits waiting to be plucked. There was, though, that curious and unmistakable scent that somehow blended with those smells: the earthy and briny essence of bulad. It was the scent that reminded us that we were, after all, back residing in the family compound.

Our decision to return was met with raised eyebrows from certain relatives who suspected ulterior motives. Perhaps it was beyond them that a move like that would be done purely out of gratitude and love. We moved houses twice within the compound, strategically distancing ourselves from the main grandparents’ house, and instead just dropping by it to check on grandma during meal times. This was a way to debunk the misconception that our family was profiting from our stay there. I find it funny though, how those who had a lot to say about our presence in the compound remained mum when presented with the opportunity to move into the main house and do the care work themselves. As if the internal drama within the gates of the compound was not enough, the city was yet again thrown into turmoil.

On September 9, 2013, we woke up to the sound of helicopters hovering dangerously close. It was the recurrence of a nightmare. But unlike the 2001 MNLF standoff, this one turned into a bloody drawn-out siege that lasted almost three weeks. This time, the MNLF swiftly seized control of several barangays, transforming them into their impregnable encampment. Their grip on the territory was bolstered by the strategic use of hostages, turning them into human shields, as well as abundant supplies of food and other necessities stashed away in abandoned homes.

Five barangays were raided; civilians, MNLF fighters, and state forces were killed; thousands lost their homes and were displaced. Tugbungan shared borders with two of those barangays. The possibility of the siege spilling over into the family compound was very likely. By then my grandmother was in frail health and already bedridden. We had to find ways to make sure she wouldn’t hear the gunfire or bombings, or else it would cause her blood pressure to spike. In the event of MNLF rebels infiltrating the compound, my father and I agreed that he would remain with grandma in the bedroom while the rest of us should hide. It was impossible to move grandma and it would be too suspicious if no one else was with her. Papa showed me a hiding spot in one of the storage rooms and he made me promise to make sure no one made a sound if we ever had to proceed with that plan.

I stood there, unable to utter a word, just absentmindedly nodding to Papa’s instructions. I remember thinking how my grandma once told me that that room used to be a storage space for arms and weapons. Back when my family’s fishing boats still plied the waters of the Celebes Sea, they had to arm themselves in case of pirate attacks. The room had always smelled of gunpowder, acrid and sulfurous. The smell of death hung in the air like smoke.

Pilar Street

More than 10,000 houses in nine barangays were razed to the ground, forcing 116,000 people to flee their homes. Five days into the siege, there was still hardly any news about it reaching the major networks in the country. And just when the siege finally came to an end—after three long weeks—the Philippines was battered by Super Typhoon Haiyan. This meant that rescue and recovery resources pivoted to the typhoon’s aftermath, leaving Zamboanga to grapple with its rehabilitation independently. The next year was an exceptionally tumultuous one for the city, riddled with petty crimes and violent “shoot-to-kill” incidents. Human life held little dignity; survival took precedence over all else.

In the wake of war, several informal settlers moved into the family compound, altering the surroundings we had known so well. With Lola’s passing not long after, the obligation that tied our family to the compound was severed. At that time, only my parents and little brother were left in Zamboanga. I remember receiving a phone call from Mama when she told me, amidst sobs, that the kamalig was gone. In one blink, all that hard work and history was but a pile of timber and rubble. The absence of the acrid briny smell of bulad in the place made the loss more palpable.

So, our family journey led us back to downtown pueblo, to Pilar Street, and an apartment complex my parents once called home. The landlady, who knew them when they were a young couple waiting for their first home to be completed, was more than happy to secure us a spacious two-bedroom unit. It was just the right size, and its being in the city center meant that all necessities were just a 10-minute walk away. Being away from the family compound also meant we had the peace and privacy we used to enjoy back in Pasonanca. Coincidentally, the apartment was housed in the same building as a renowned satti eatery in Zamboanga. The smell of the flavorful broth wafted into our home every morning, its invigorating aroma marking the start of each day.

As early as four in the morning, one could already hear the patrons of the eatery scurrying around—students, young professionals, laborers of the nearby port, fishermen, and jeepney drivers. Everyone was there to enjoy the dish and let the piping hot bowl of satti take center stage. A symphony of scents would emerge: turmeric, curry, peppers, lemongrass and garlic intermingling, seducing the senses with promises of warmth and flavor. Echoes of Malaysian and Indonesian satay were present, yet this Tausug dish had claimed its distinct identity: halal meat skewers chargrilled to perfection nestled beside a bed of sticky rice called tamuh, and every single square inch lavishly draped in a sweet and spicy crimson sauce.

To avoid the early morning rush, my parents would often order a huge bowl of satti for breakfast and have it to go. Upstairs, in their cozy apartment, Mama would sometimes serve it with shredded pieces of bulad. I suppose, no matter what, bulad would always be a mainstay at home.

Where I Come From

I am from big Sunday brunches in the family compound: my siblings, cousins, and I wearing our pristine church clothes and being on our best behavior, while the adults take turns in commandeering the kitchen. I am from dishes made from what the sea has to offer, cooked in ways known to the coastal towns of Iloilo, Cebu, Cotabato and Zamboanga – from all the dishes that somehow made their way to our shores. I am satti for breakfast, Knickerbocker for dessert, and marang any time of the day. I am from several homes where the hint of bulad lingered in the air.

I am from that cozy little house in the hilly terrain of Pasonanca, that part of Zamboanga that smells oddly of pine cones nestled way up in the city, kilometers away from downtown pueblo. I am from wild greens, calamansi, atis and peppers, all grown in the fresh dirt, under the blazing sun, in our tiny yard.

Then I am from that antique bungalow with its one room that used to be solely for storing arms, then that two-floor building with creaky floorboards and locked storage rooms, then that two-bedroom apartment downtown that finally spelled quiet for us.

I am from homes that were cherished then left behind, from feeling lost for almost a decade in an urban jungle. I am from that frequent need to move homes—Quezon, Dumaguete, then Davao, but always finding myself returning to Zamboanga.

I am Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Binisaya, Hokkien, English, with snippets of Tagalog and Tausug, all rolled up, complexed and compounded, in one sentence. I am from constantly-shifting linguistic gears, depending on whom I talk to. I wonder if I have a motherless tongue—or one with multiple mothers. I am quirky Math trivia from Papa and tales of seafaring from Mama before I go to sleep, both of them weavers of wondrous and enchanted tales. I am learning at an early age how much each type of fish would sell depending on the season, and knowing how to properly scale and clean them even before I learned how to cook rice.

I am from the people of Pasonanca, Tugbungan, the rapidly-evolving pueblo, and little pockets of different cities that refused to change. I am from the kitchens and couches and spare rooms of the friends I met in college and the strangers I encountered on my travels. Those who overwhelmed me with joy and food and stories and singing. Lots of singing.

I am from the well-worn Kodak albums that I still take with me wherever I go, in new cities I’ve learned to call home, sorted and filled and labeled by twenty-year-old me. I keep those albums in a box, under my bed. And I let all those lost faces drift beneath my dreams.

© Sigrid Marianne Gayangos

Commissioning editor: John Bengan