Faces of Maitum

Photo: Maitum Information Office

Maitum | 2,416 words

Translated from Filipino by Melona Grace Mascariñas

After All Souls’ Day, in the year the archaeologists dug in Ayub Cave for the last time, I snuck inside a sack of bananas my grandfather was bringing back to Maitum.

I would have been five years old in my earliest memory about Maitum, the hometown of most of my grandfather’s and mother’s kin. Like most early memories, this one is a collage of anecdotes from people who claim to remember. Among them are my parents, who often told this story to relatives who visited our house in what was then known as Dadiangas, the nearest city to Maitum, where I was born and schooled.

They say my grandfather was on his way back to Maitum after a week-long visit in Dadiangas. He would never miss the harvest of rice or durian or cassava or whatever it was that he had planted. That was how I’d always pictured Maitum, a vast field lined with rows of different crops. From the moment he arrived in Dadiangas, the first thing my grandfather would talk about was the prospect of going home to Maitum.

In the year of this memory I was in kindergarten, but there were no classes for more than a week. I can’t remember how I got the idea to go with him, but that’s what happened: when I saw my grandfather preparing to leave, I snuck inside a sack filled with bunches of bananas he was bringing home. I pretended to be a statue. Quiet as stone. Even when my grandfather started to carry the sack out the house. Even while I was loaded under the seats of the passenger van bound for Maitum. They say I only moved and revealed myself after several minutes, when I felt we were already a good distance away from Dadiangas. The passengers were caught by surprise, and some of them laughed when they saw me. I was bulyagon, they said, a naughty child who tags along without invitation, like an amor seco that clings to clothes unnoticed.

“Litseng yawa!” my grandfather cursed the devil. He didn’t have money to pay for my fare: he always brought just enough. Fortunately the driver didn’t mind. After all, a child could sit on someone’s lap. Nobody had known a boy was hiding inside a sack of bananas. If only it were that easy to beget children, said the driver, he and his wife would surely start a banana farm. The passengers laughed even more, while my grandfather couldn’t do anything except take me to Maitum.

*

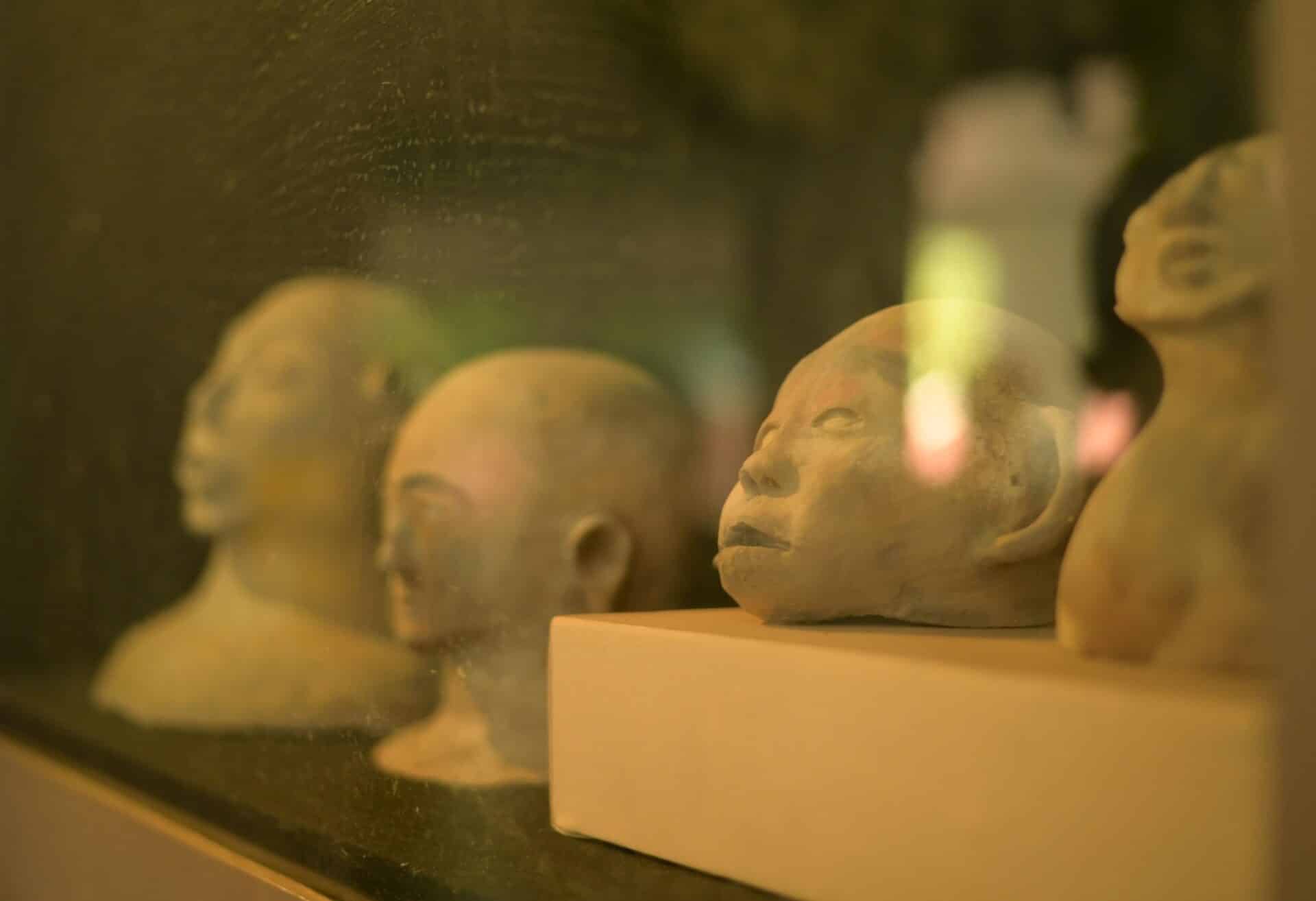

I have no memory from my childhood about the jars with faces in Maitum. I only learned about them in high school, that this small town in Sarangani was famous for these jars. They’re believed to be secondary burial jars that belonged to ancient peoples in southern Mindanao, and they’re not like anything else in Southeast Asia.

According to a well-known account of how they were found, a geologist and an archaeologist talked over the phone in 1991 about jars with human-like shapes lying in Ayub Cave. The jars were supposedly uncovered during a hunt for the rumored treasures of the Second World War. Three days after that call, the archaeologist received photos of the said jars. After that he sought funding for an excavation, and then days after All Souls’ Day in 1991, he traveled to southern Mindanao. Three phases of excavation had to be done before its completion in 1995, after which most of the possessed jars were placed in the care of the National Museum.

Not all the jars they took had faces, there were many other things that they found in the cave. The archaeologists systematically listed these things—counting how many heads, shoulders, arms, chests, and other body parts were retrieved. They also found beads, bracelets, scoops, metal implements, and other burial goods. They described the designs, colors, and similarities with other burial jars. Even how the faces were molded, or how the parts adhered to the jars.

I’ve stared countless times at the faces of the jars in the National Museum in Manila, or read the labels in the exhibit at the town hall of Maitum. I’m curious about their stories, but indeed the jars cannot speak even though most of them have mouths.

*

My grandfather wanted to have a statue made of him from head to chest. He always told us that in his last years. He would have had it erected on his field in Maitum so that passersby could always see and remember his face.

It didn’t happen.

Or, we didn’t make it happen. Because who does that in a field of crops? When I told this to my cousins during one occasion in Maitum, they laughed. “Just like a politiko.” It was easy to find grandfather’s fields anyway. Straight and uniformly-spaced were his fields of coconut trees or cassava or durian or anything that was being grown. The fields showed how prudent my grandfather was, why he took so long to finish planting.

My siblings say I inherited my talent and fondness for growing things from my grandfather. Now I am tending marang, avocado, durian, jackfruit, soursop, and other fruit trees. When I was a child, I used to find little papaya shoots that had sprung from the soil where their fruit seeds had been discarded. The first ones I deliberately planted were monggo seeds for a school project. I was quickly convinced that growing monggo was easy: the seeds would start to sprout in just a day or two. But one day, a strong rain drowned the scrawny bodies of the monggo I had planted. Almost nothing survived. Afterwards, I developed a habit of crying whenever it rained, not because we were prohibited to play outside, but from being reminded of my plants drowning.

Maybe my grandfather was thinking along the same lines whenever he rushed back to Maitum. Perhaps he worried that his seeds would get washed away by rain or eroded with the soil, which would ruin his straight rows. So every time he went to Dadiangas, we knew he wouldn’t stay long. He’d come home after a few days, because his life went as his plants’ lives went in Maitum.

But on his last visit to Dadiangas, he wasn’t able to return. He stayed for almost half a decade, imprisoned in the house. He had slipped one day, and walked with difficulty subsequently. He always sat in the room kept just for him, in his wheelchair, constantly looking at a framed embroidery of horses hanging on the wall. On some days, he would say a woman named Marga was riding one of the horses and they were on their way to the mountains. And on other days, he would cuss, “De puga! One day, one eat,” because he always lost track of the meals he ate on any day. And there were those days when he would ask what day or month it was, and he’d remind us of the crops he had left behind, and that he needed to go home. We kept giving him the same answer: we’d take him to Maitum once there was time and his knees were strong enough. But then the pandemic got to us.

My grandfather was not able to return to Maitum. He died at the age of 92 in 2022, in his sleep, after a few days of losing his appetite.

*

In my memory of going to Maitum for the first time, my grandfather left me straightaway at the house of one of my aunts, at the base of the mountain. I was told to stay there so I could have food. “Where’s grandpa’s house?” I asked my aunt, and she pointed at somewhere on the mountain.

The sun had just risen the next day when I went looking for my grandfather’s house on the mountain. It was the only house there, more of a hut, almost entirely made of bamboo, surrounded by trees. When I went inside I saw my grandfather wearing a hat and carrying a bolo. He just looked at me, then he split a sugarcane. “Here,” he passed the cane to me, and sent me away because he was about to go out to farm.

I was heading down the mountain chewing the cane when I ran into a child who was the same size as me. I can no longer remember his face, only his name because it was the same as mine. “Cane?” I offered him, then he split the cane on his thigh and kept half for himself. We talked while we chewed, and he invited me to wander around the rice fields. Mud enveloped our feet. We crossed a dike. We folded the leaves of makahiya. Mooed with the cows. Until we realized the sun was already setting. He didn’t want to go home yet, but I was worried that my aunt would be looking for me.

I don’t know how I knew the way back to my aunt’s, but she welcomed me with her eyebrows meeting in the middle of her forehead. Where had I gone, she asked. I told her I went to my grandpa and then played with Michael. “Who’s Michael?” I described him to her, but there turned out to be no Michael among the neighbor’s children. “Probably not like us,” she said.

That might have been the first time I learned that some beings can’t always be seen. I recall a story about my grandfather’s childhood. Those that were dili ingon nato, not like us, really wanted to play with him, but he was only allowed to go out in the daytime, and these beings were afraid of the sunlight. So they would visit him when the sun wasn’t at its peak and they would narrow their eyes to avoid the sun’s glare. My grandfather mimicked them, until he became old and they stopped playing with him. They never showed themselves again, but from that time onwards my grandfather’s eyes stayed squinting.

*

Even narrower than my own eyes are the eyes of one of the jars in the National Museum. We don’t have the same eyebrows, though, because mine are shaped like mountains, just like my grandfather’s.

Archaeologists have observed that the faces on the jars are never the same. Some of their theories claim that the figures on the jars were the faces of the buried; that their size, design, and accessories imply the status in society of the person buried in the jar; and that there was equal treatment of women when it came to burials because figures with breasts were found.

There were many tales spun, but not one was for certain.

Many became interested in visiting Maitum, especially when news came out about the jars and other artifacts found in two other caves. But the fates of all the artifacts would be the same: they were stolen and sold from place to place. In 2008, twenty-two bags containing fragments of faces, eyes, ears, mouths, and other jar parts were confiscated, about to be sent to a company in Manila selling antiques. The archaeologists had trouble piecing the broken parts back, including what could be discerned about the jar makers’ ancient lives.

The caves have always been difficult to go to. Since the 70’s, conflicts between armed groups have raged in the mountains of Maitum as a part of the other wars waged in Mindanao. Consequently, almost no studies could be done of the jars.

Except for some elderly people and employees of the municipal office, only some residents of Maitum now remember the discovery of the jars. All most of them know: jars with faces were found in their town. And there’s a handful who say they have relatives or acquaintances who had gotten pieces and sold them away.

All that’s certain, now, is this: never did they see Maitum again, those jars that were taken because they had faces.

*

I asked my grandfather several times about the jars with faces. He remembered them, and he knew how to get to Ayub. There are still caves that haven’t been searched, that are suspected to contain jars too. But he never had any interest in them. He said we ought to let the dead keep their peace.

But since I grew up and have gone home to Maitum so many times, I’ve noticed how the mountains there could never keep their peace. Wars go on. Treasure hunts continue, whether for jars or for whatever is still left of World War II. Slowly, farm lands are starting to disappear.

I have also slowly come to understand that, possibly, a few of, if not all, the details of my first “memories” of going to Maitum aren’t true. Especially after I learned that I’d gone to Maitum several times as an infant, according to our relatives’ stories. So I probed my parents: why would my grandfather bring bananas home when he was the one delivering his harvested crops from Maitum? And how did he or anybody at home not notice that there was something odd about the shape or the weight of the sack? And just how was I placed under the seats of the van? And how come I’ve never seen my namesake again, Michael?

They have plenty of explanations, such as how we had some banana trees planted in our backyard that time, and that I was a pretty skinny kid who could easily slide into any sack, crevice, or jar, and that I actually remembered it wrong, and that it wasn’t Michael but a relative I had played with. My forehead wrinkled at these, but eventually, I simply let this memory stay.

Meanwhile, my grandfather’s remains will forever stay in Dadiangas, far from Maitum. He was placed inside a coffin that was slowly lowered and buried in a small grave. He has a small tombstone on which his name and the length of his life are engraved. It doesn’t have a face. It’s just one of many tombstones in a row, almost equally distanced, within a vast yet enclosed resting place. Outside, heat from the cemented roads seeps up, and a fine layer of dust covers the rest of the city. It cannot keep its peace, much like me, in my first memory of leaving Maitum for Dadiangas, on the Monday after All Souls Day, in the year the archaeologists last dug in Ayub Cave.

© M.J. Cagumbay Tumamac

English translation © Melona Grace Mascariñas

Commissioning editor: John Bengan