How Much of the City Are We Willing to Lose?

Photo: James Dorevski/Unsplash

George Town’s city center | 2,500 words

The trees on my peripheral vision are spaced out along the street and so few in number I can count them on one hand. The sky is a melancholic blend of blue, amber, and purple. Pigeons coo on power lines as sparrows chirp and peck away at the street floor, exchanging bird-chatter before the crows arrive. The sea is a calming force in the distance, unthreatening, roaring only at high tide. A gentle breeze whispers through these streets; a thick stinging mud-salt smell mingles with the fresh air.

These things occur around me between 7 and 8 a.m. each day, at the intersection of Jalan Pintal Tali and Lebuh Campbell, as the inner city of George Town awakens. Any later, all these transitory sights, smells, and sounds are replaced by a deluge of traffic and people.

As I linger, a man appears riding his motorbike toward Lebuh Chulia. Leaves from a bundle of bak choy hang out from the sidecar as the plastic bag flaps. His collared t-shirt is slightly tattered, and he wears an unbuckled helmet. He takes a deep puff of his cigarette before flicking it on the street. He notices another man and yells out, “Rahman!” He raises his hand and nods his head. I follow the path of his palm and see a man whose face opens up in a smile. He yells, “Chan!” and holds his hand up in return.

Chan goes off to make his first delivery. Soon he will enter the scene again, but for now all that’s left of him is an oiled, masculine, woody aroma.

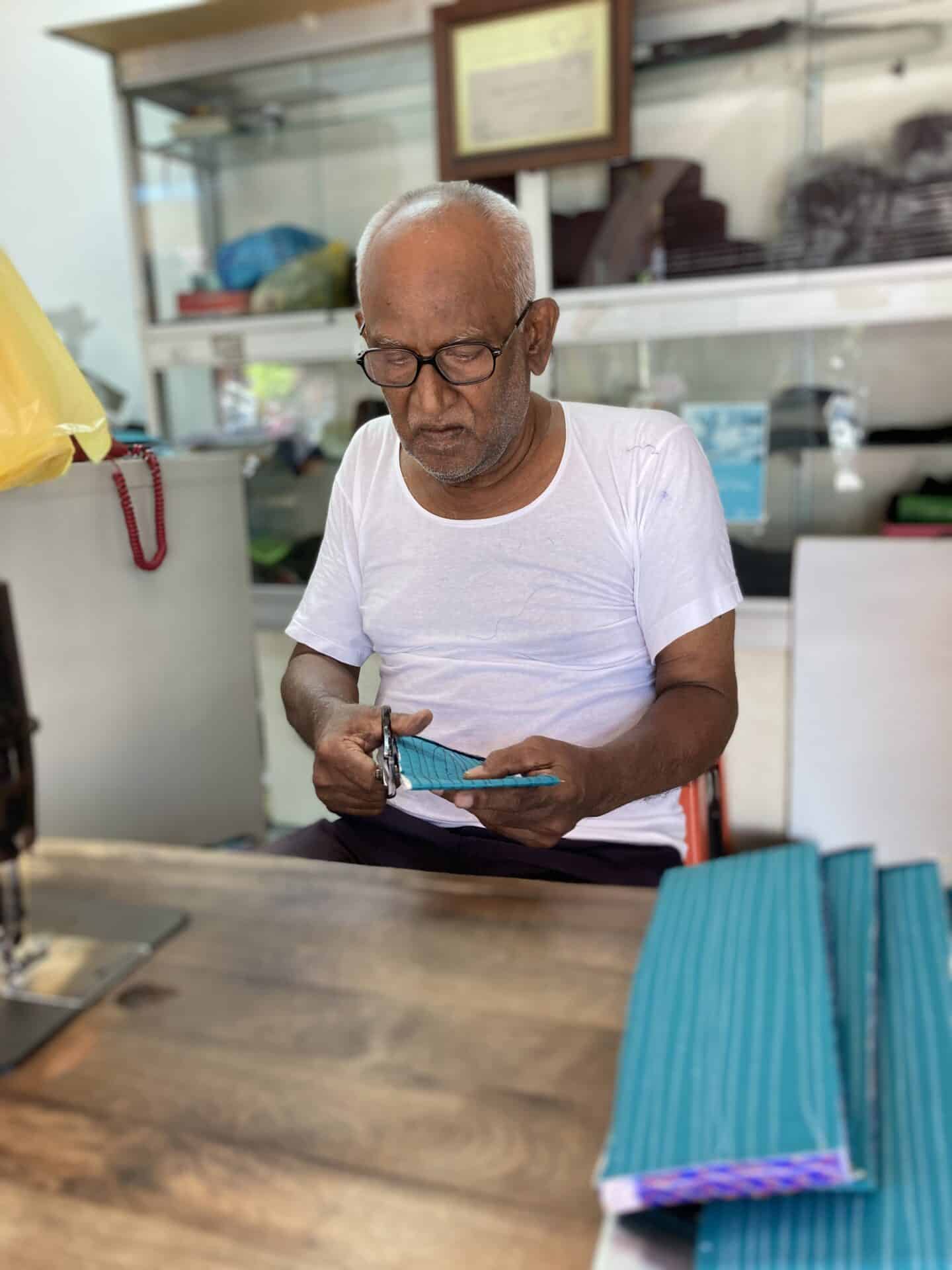

As his motorbike sputters down the street, I follow the sparks of bright amber from the tumbling cigarette butt to its final resting place, a pile of dried leaves by the hole of a drain. Rahman, a council worker, remains silent amidst the scratchings of his long lidi broom as it grazes the paved street floor. He wipes his face with the towel around his neck, white with blue edges and red Chinese characters—The Good Morning Towel, a staple for people who work with their hands. He gathers a pile of leaves, gravel, dust, and cigarette butts into a metal dustpan and pops his collection into a big rattan-weaved bin that rests on a wheelbarrow. He is small and thin, with a gentle determination.

For a time, we are the only people at the intersection—Chan, Rahman, and me—three individuals, of three ethnicities, from three generations, with very different lifestyles and practices, finding ourselves in a shared space, but only for a moment. Soon, Chan and Rahman will become known as “uncle” and “pak cik” to me, though they will never know me by name. And each morning, for a moment, we will hold our hands up, nod our heads, and bid each other a good start to the day.

Gradually, the city begins to stir. Roller shutters of shophouses rise and smack to the top as business owners, primarily men in their fifties, prepare to welcome customers. They are usually the earlier ones along the street, with tiffin carriers in their left hands and a couple of newspapers folded under their arms as they turn keys in locks and raise the doors expertly with one hand. Some will go on to have breakfast with their friends at local cafes before the crowds arrive at 10 a.m.; others sweep their storefronts, pushing away dust gathered through the night for people like pak cik Rahman to collect and clear out.

Elderly residents living in heritage shophouses open their wooden windows as they greet the hawkers pushing their carts towards Lebuh Kimberley. One or two cars pass by, but most vehicles on the road are motorcycles, uncles heading over to kopitiams for breakfast, or older couples on their way to their weekly run. Stainless-steel spatulas begin clanging against the handles of cast iron woks as the hawkers prepare char koay kak and vegetarian mee hoon.

Within the inner city is an understanding and an ecosystem of its own. There is a deeply-ingrained knowledge of people and space, erasing invisible boundaries and carving moments of belonging among one another. Residents, business owners, hawkers, traditional practitioners, delivery men like uncle Chan, and council workers like pak cik Rahman, have lived and worked in the inner city for decades, giving life, character, and identity to George Town. And I have the privilege of being a quiet witness.

*

In my academic writings I use words like transnationalism, interculturalism, cross-culturalism, super-diversity, and metrolingualism to describe the city and its people. These are buzzwords, really, good for search engines and only relevant to a small circle. But the word I long to use to describe the inner city is kampung.

In the Malaysian context, there seem to be multiple meanings associated with the term kampung. Google it and most images will show a wooden house on stilts surrounded by lush greenery and paddy fields. Dictionaries might describe it as a Malaysian “enclosure” or “village settlement”, often in rural settings as opposed to the city. Sometimes, also, I hear people use the word kampung to describe a kind of attitude or behavior, stereotypes from sneering urbanites who think kampung people are somehow less-than in thought, speech, and wealth.

Then there seems to be another meaning, which I wish was my genius speaking, but all credit is due to a 20-year-old girl I talked to recently. She talked about how at noon every day, from the corner of her classroom, she would see how worshippers from different religious spaces would shake hands and bid each other well wishes. She talked about how the elderly, regardless of ethnicity and background, greeted one another with kindness and familiarity. “Everyone knows each other,” she said, “because they want to.” She described the city as a kampung, meaning not that rural image, and not, in any way, that negative connotation, but as a feeling of togetherness, openness, and oneness.

*

I realize just how true her words are. As I walk the city’s inner lanes, I become more aware of this sort of feeling amongst its people. Throughout the inner city are aunties and uncles, mak ciks and pak ciks, akkas and annans, kakaks and abangs who create spaces of belonging for me and others who work and live here.

Aunty Anne, for example, sits along the intersection of Lebuh Penang and Lebuh Pasar, or Little India, as the locals call it. While she sells masala tea to passers-by, she keeps an eye out for traffic and is always ready to help those who need it, no matter who they are. Like the time she stopped traffic to help the old man on crutches who fell while crossing the road. That old man stands by the junction at the entrance of Sri Anandha Bahwan, a permanent fixture for over ten years now, palms curled out to everyone who walks by, waiting for any Good Samaritan to spare a ringgit or two.

He says he misses the good old days when he could sit with his Chinese and Indian friends, and it wasn’t a problem. What they ate and where they ate was never an issue, until suddenly it was. And slowly, he began to eat his meals alone.

Little India is one of my favorite spaces to walk through in the mornings. Along the street are stains of turmeric water thrown religiously every morning to usher in prosperity for the day. The uruli is placed at entrances to welcome guests—roses and chrysanthemum flowers of bright yellow, orange, and red, and a candle in the middle, floating in bowls filled with water. The melodious ringing of handbells fills the street as business owners chant morning prayers outside their premises while Indian restaurants and cafes grill thosai and roti canai on gas griddles, the aroma of spices mixing with jasmine and incense. Every time I walk these paths I am reacquainted with aspects of culture and heritage which people are ever-willing to teach.

Along Love Lane, there is a mak cik and pak cik who sell the best (in my opinion) nasi lemak in George Town. Coconutty rice topped with sambal that’s the perfect blend of spicy and sweet, with plenty of ikan bilis and roasted peanuts. When I worked at the local church for a year, this was my once-a-week breakfast treat. You have to be early, though, because most of the food is sold out by 8.30 a.m., bought by hungry students on their way to the local primary and secondary schools around the corner.

Then there is Uncle Sunny, who invites me into his home in the Clan Jetties and shares his family’s history. He talks about his best friend, who speaks Hokkien like it’s his first language, even though he is Indian. He tells me how he likes surprising his other friends with this. Uncle Sunny says he sometimes goes to pray at the Sai Baba temple, and he tells me that he welcomes every religion and seeks to know more. He steams a red bean pau for me, and we eat together as we watch the tide rise—a 60-year-old man and a girl sharing space and food while he reminisces on the simplicity of the past.

At a petrol station, 80-year-old pak cik Sulaiman tells me he moved to George Town from Taiping when he was six. He’s lived in the city for 74 years, never married, no children. He only speaks English, yet he is persistent in telling me he is proud of his Malay–Thai roots. He says he misses the good old days when he could sit with his Chinese and Indian friends, and it wasn’t a problem. What they ate and where they ate was never an issue, until suddenly it was. And slowly, he began to eat his meals alone.

Pak cik Sulaiman tells me he’s seen how young people today are not as friendly as they used to be. He tells me to remember to be kind and good and to always say hi to him whenever I come by. He tells me not to be like other young people. And while I giggle at his insistence, I ponder, regularly, on his words, and the shifts he has seen in the city and our society.

*

In its yesteryears, the inner city felt like home. Yes, it was historically a trading post, but sojourners became settlers who built homes and raised families. Festivals were celebrated, and the town was decorated as a shared community event. People had pulleys running down the walls of their homes, exchanging rice for milk. People back then spoke a different language—a language of community, dependability, loyalty, friendship, and togetherness. It was the language of satu kampung, one kampung.

Today, the language of the inner city has changed. For one, there appear to be several other identities now attached to this space—a historic city, a heritage city, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, an emerging art city, a living heritage, a creative digital district. Because the inner city is now also a tourist destination, there are new terms to capitalize on (apologies, tap into) our artistic-cultural offerings. Yet, these are primarily a matter of the promotion of street mural art and our heavily-Englished iron-rod sculptures. Artisans who actually create unique, skilled and creative work now have to deal with all these other things that say they are “artisanal”. Very vogue indeed.

On an average day, the historic buildings, whether pre-war shophouses (especially those along Lebuh Armenian) or remnants of colonial buildings (along Lebuh Pantai), are ideal sites for wedding photography. In the past decade, there has been an influx of cool, indie-type cafes and contemporary fine-dining restaurants blossoming in these spaces. They have closed doors and fancy signboards, sometimes with names no-one can really pronounce, but who cares? They serve a cup of coffee at an average of RM16 and a “krus-ant” and “pan a-u chocolate”, which is always good for the gram. Don’t you know? Everyone’s an influencer now.

So there are words like gentrification and UNESCOcide which further spur discussions about the inner city, what we should do and what we shouldn’t do. Yet while we periodically have these conversations, the people who actually live and work in the city, especially those of a particular generation, have to grapple with, and accept, the consequences of our changing times.

It’s alarming to know that the people and things that make the city a kampung now struggle to survive.

*

I do not go to the inner city for three months, then return. As I walk along familiar paths, bumping into people I know, and searching for those who are no longer here, I realize just how much things have changed, even in this short time.

There are more new shops opening up and old ones closing down. There are different people interacting along the street and a heightened presence of tourists from cruise ships. All predictability dissipates as I become more aware that, though some people remain, there is a strangeness and unrest now negotiating with the familiarity and belonging. How short a time, yet how quickly these feelings have shifted.

Even now, as I write this, I wonder whether it is some people being no longer here, or some spaces being not as they used to be, or certain smells or sounds being replaced that most makes me feel like a stranger.

Walking through its streets, I realize that the city exists in flux, and to experience the city is to constantly negotiate between the past and imagined futures, sprinkled with promises to quieten the changing tides of the present.

And yet, every time I see uncle Chan, pak cik Rahman, aunty Anne, pak cik Sulaiman, the homeless and street beggars, the man with fantastic plaited hair who stands by the street and stares into space, the couple who sells nasi lemak along Love Lane, the women who inhale cigarettes for breakfast by the alley, the Punjabi man who owns a bar, the pak guard who fistbumps me whenever I pass by Whiteaways Arcade—whenever I see these people, I am drawn back into the familiarity of a home.

Even within the changing scapes of the city, these people wear their roots and histories around their necks, (re)creating prolonged moments of togetherness and acceptance through the sharing of stories and through lives cocooned in remembering what it means to be a community.

*

The kampung of my adulthood differs greatly from the kampung of my childhood. But the feeling of home remains.

The city is a kampung, built on the backbones of people who work with their hands and have toiled to build the inner city into what she is today.

The city is a kampung, with lives tethered by friendship, loyalty, kindness and goodness to one another.

The city is a kampung, a shared heritage of home and community for all to discover and belong.

How much of that are we willing to lose?

© Miriam Devaprasana

Commissioning editor: Anna Tan