In the Mood For Kopitiam

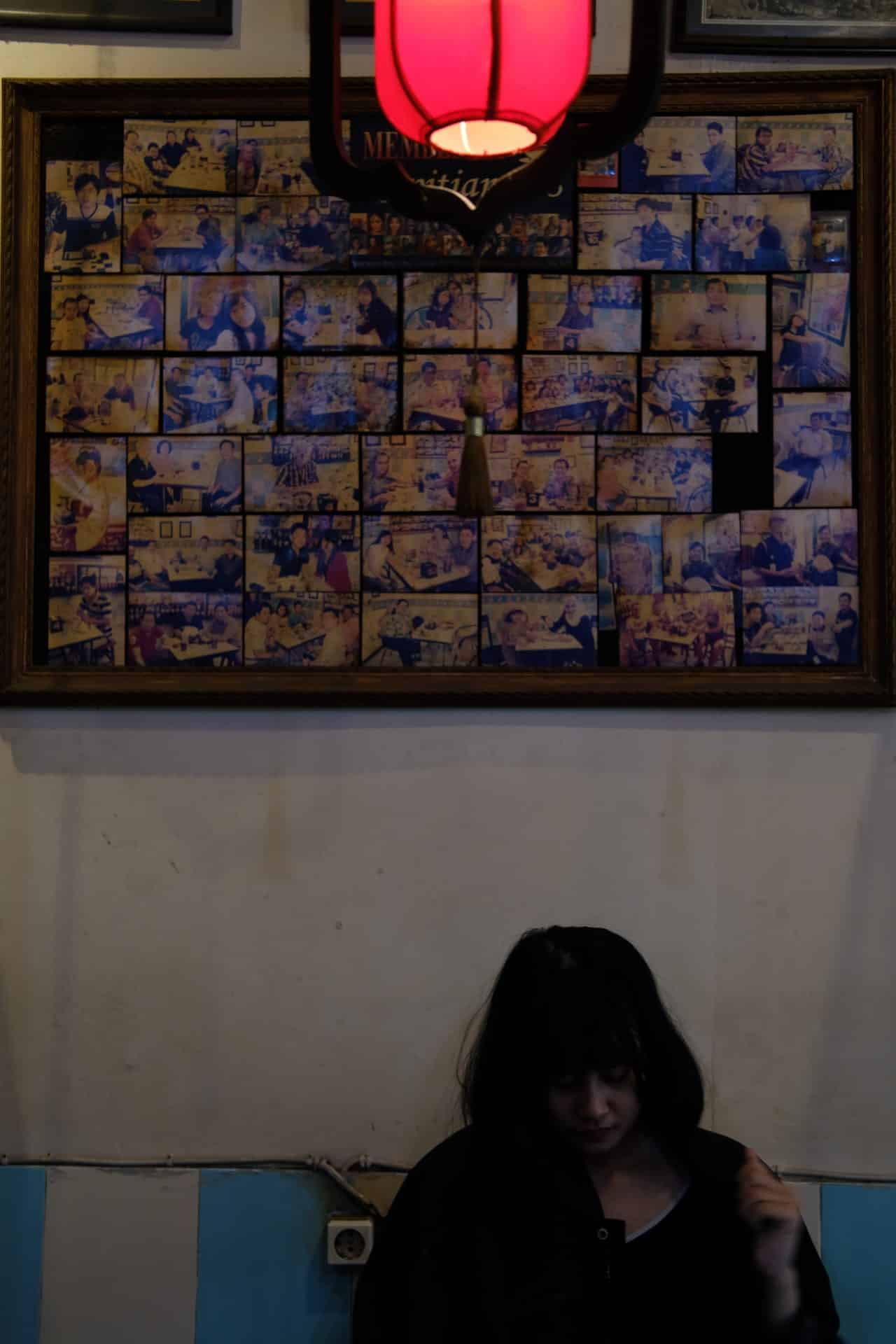

Kafetien 88. Photo: Vema Novitasari

A Chinese coffee-shop in Surabaya | 2,720 words

Translated from Bahasa Indonesia by Lise Isles

Kafetien 88 is in the old town of North Surabaya, on Jagalan Street. In this area, which was the old centre of trade during the colonial era, the pulsing energies of Tanjung Perak Port, the offices of state-owned agricultural and shipping companies, a major train station and several markets can all be found amidst dense residential neighborhoods.

I first visited Kafetien 88 in 2012 with one of my exes—let’s call him “B”. At that time it was still called Kopitiam 88. Later “kopitiam”—a word for Chinese-influenced coffee shops or cafés, coming from the Malay “kopi” (coffee) and the Hokkien “tiam” (shop)—was patented as a brand, so they had to change their name. Even though “kopitiam” is a widely used word in Indonesia. But anyway: let’s leave that irritating issue behind.

“B” and I agreed to have lunch at Kafetien 88. As a poor student without my own wheels, eating in North Surabaya felt like the journey of the Monkey King in search of the holy scriptures. Adding to the sense of adventurousness was the café’s location in a trade and commercial area which was frenetic by day but eerily quiet by night—we’re not talking here about a renowned foodie district or fashionable young peoples’ area.

The communities of North Surabaya tend to be more heterogenous than those in the centre of the city. Large numbers of Javanese, Madurese, Chinese-Indonesians and Arab-Indonesians all live close by each other. Near Kafetien 88 is a fleamarket dominated by Madurese, the Chinatown area of Kapasan, full of Buddhist and Confucian temples, and the grave of Sunan Ampel that’s popular with religious pilgrims, disproportionately Arab-Indonesians.

With the area’s demographics and characteristics, the target market of Kafetien 88 is quite clear—Chinese-Indonesians, businesspeople, traders, and workers from the surrounding offices. The state-owned companies are just five minutes away, Tanjung Perak itself a mere ten.

As I entered the café that first time I heard playing from the sound system “Hau Siang Hau Siang” by Vicki Zhao, from the old Chinese TV show Romance in the Rain. I looked at various antique objects scattered around as ornaments: old posters and photos on the walls, an old bike, an abacus, a radio, an ancient television with wooden sides, plus old kitchen implements sitting on a shelf. Paint was peeling. There was a dark stain on the ceiling from rainwater. With the passage of time the window-panes had gone cloudy and blurry. Humid air mixed with cooking aromas coming from the kitchen. The café, I thought, was like a dating-spot in the films of Wong Kar Wai. Any enthusiast of the films Chungking Express or In the Mood for Love would be totally happy dining here.

“I am sad and well fed”, I thought as I sipped my iced teh tarik. A plate of barbequed chicken and rice I had just polished off. For someone who’s had quite a few partners, my taste in food is notably monotonous.

We sat on chairs whose seats and backs were made of thin multicolored rubber cords. It had been a long time since I’d encountered chairs like them. An age ago I’d seen them on our neighbors’ terrace. Families used them with the utmost caution so the rubber cords didn’t snap or hang down like the long aerial roots of banyan trees. Back then owning such chairs was an indicator of how respectable a family was. My own family never had beautiful but easily-broken things like that.

When combined with the café’s tables—wooden, except for their glass tops—the décor was nostalgia-triggering. The feeling was like stopping in for lunch at the house of your mother’s uncle who’s a retired employee of an oil company. The tables and walls were decorated with slogans and proverbs, pearls of wisdom, inspirational advice or anecdotes in Bahasa Indonesia: pictures accompanying the words appeared to be taken from Microsoft Office 98 stock images. The whole vibe felt the rough equivalent of meeting Mario Teguh, the 60-something Indonesian motivational speaker who has prominently reprimanded young people, except in a friendlier form—all the aesthetics and ethos of baby boomers were present here, yet manifested in a way that didn’t make me feel I was being lectured.

The café served up various Malay dishes like nasi lemak, nasi timbel, kaya toast (with coconut jam as filling) and mie lendir noodles. Indonesian dishes like soto, sayur asam and ayam bakar were available too.

According to my companion, who’d already made a pilgrimage to Penang, this place was similar to the kopitiams of the Peranakan Chinese community in that city. “I usually get black coffee and kaya toast”, he said. “The coconut jam here tastes completely different from the coconut jam sold in supermarkets: it’s homemade”. I’ve never been to Penang: I simply listened to him talk while nodding in admiration.

Another thing I noticed immediately about Kafetien 88 was that the servers were fluent in Madurese. I heard them speaking between themselves using this language: I could even understand a little of their discussions. Occasionally, I heard melodic recitations of the Koran coming from their phones. A Chinese-style café, with Madurese waiters, selling Malay food. I thought: this slaps.

My very first order at Kafetien 88 was a plate of barbecued chicken and rice and a glass of iced teh tarik. I had worked as a liaison officer at a sports event that day and the pay was pretty decent, so I was more relaxed about eating at a place whose prices were beyond my usual student budget. During the meal we chatted about my dissertation. As we were leaving, I promised myself I’d be back.

It’s actually very easy to appraise whether a particular restaurant is worth visiting or not. A restaurant or café that’s popular with Chinese-Indonesians, families, old people and office workers usually has good food. Places that are popular with the Instagrammable community generally see tastiness as a second order issue, with the priority given to aesthetic interiors. Kafetien 88 fits in the first category, and that alone was motivation for me to return.

When my relationship with B finally ended at the end of 2012, I came to Kafetien 88 with my next boyfriend: let’s call him “C”. What can I say: I’m one of those people who doesn’t let sentimental memories get in the way of a good meal. Returning to a place where I’d spent time with my ex wasn’t difficult for me, then. Although I was accompanied by a different person, I ordered exactly the same thing: iced teh tarik and barbecued chicken with rice.

Eventually I got a job in an office close to Kafetien 88: my route home all but passed it. Not only was the café easier to get to, but with my new salary it no longer felt so expensive.

After five years together, my relationship with “C” ended in 2017. But as time passed and various things around me changed, I returned again and again to Kafetien 88 with various people: office colleagues, suppliers, and my family.

And, months before the pandemic smashed up our lives in 2020, I also went there with my next boyfriend. Let’s call him “A”. I deliberately give him the letter “A” because, supposedly, it was he and his friends who were first to “discover” Kafetien 88 and introduce it to our wider social circle. The story is that “A” and his friends came across the place when buying a bicycle light from an electronics shop nearby. The friendship networks of myself, “A” and “B” were so tight that a culinary recommendation spread seamlessly.

The afternoon “A” and I went to Kafetien 88 I was a little lethargic because earlier I’d entered the emergency room with gastric acid. Throughout our journey there, heavy rain fell. It was like I was in a romantic drama from the ‘90s, staring at raindrops on the car windscreen.

Amidst the rain that blurred our surrounds, the unostentatious café was barely visible. The yellow lamps next to its entrance were giving off a softer glow compared to the lights set to maximum in the surrounding stores. It was as if the place was comfortable in its own skin, feeling no need to compete for attention with the new hip cafés elsewhere in Surabaya. The restaurant that night felt warm, familiar.

“A” and I had already known each other for about eight years before we’d finally got together. For seemingly forever we’d floated in the same circles and worked in the same district, even separately visited this same café. Yet it had required nearly a decade for us to be brought together here.

I still remember the color of the T-shirt he wore and the nasi goreng he ordered that day. Kafetien 88’s nasi goreng is a little different to other nasi goreng in Surabaya which is a redder color—theirs is browner, the rice softer, and it’s capped-off with a small omeletr on the side, like a strip of yellow lace. As usual, I ordered an ice teh tarik and barbecue chicken with rice. It seems human memories really are sharper when relationships are still new.

Going home, my mind wandered: if “A” hadn’t bought a bike-light in Jagalan Street, maybe I would never have known about this café. Perhaps A should be thought of as a prophet spreading a message from God, only one which had taken the form of food.

Yet my relationship with “A”, culinary prophet, was not to last.

Being broken-hearted above the age of 30—with my mind processing things with a painstaking-thoroughness in the middle of the loneliness of the pandemic—caused in me a shock of quite terrifying intensity.

I had to pass my ex’s office every day—sometimes I glimpsed his car. I went back and forth between overflowing emotions and feeling empty. I spent months wandering the streets we had walked together, as if looking for the spot where our love had drained away.

In this period, empty and dark, one place I visited alone was Kafetien 88. After the pandemic began I rarely met other people, let alone ate together with people. Eating alone when life is fine is just another normal activity. But when atop a mountain of loneliness, every mouthful was a reminder to me to keep going. I don’t remember too much the taste of what I ate. It was just a way of not surrendering fully to despair.

I realized that, in the almost nine years I had known Kafetien 88, this was the first time I had visited alone. I became aware of something no less important, too: I had almost never not had a boyfriend. I was always with someone, as if I had forced myself into continuous relationships.

I became aware of these facts to the accompaniment of Vicky Zhao’s “Hau Siang Hau Siang” which, again, was being played softly. A plate of barbequed chicken and rice I had just polished off. “I am sad and well fed”, I thought as I sipped my iced teh tarik. For someone who’s had quite a few partners, my taste in food is notably monotonous.

I started coming to Kafetien 88 around once every two weeks, sometimes only to wait for peak-hour traffic to ease. On days off from the office, I went and caught up with some work there. I began to observe the people sitting around me, even eavesdropping on their conversations. One man spent an hour on the phone discussing business. Another man I heard say, “Falling into poverty is bearable as long as my child can go to school”.

One time, a Chinese-Indonesian man, elderly, came along and sat at the table next to me. He ordered a bowl of bubur ayam, a hot rice porridge with shredded chicken, peanuts and fried shallots, plus a Chinese doughnut stick.

Intermittently I glanced over at him. He was slim. He was wearing shorts and a plain green shirt. He looked fit and spry. I noticed he wasn’t on his phone. After he’d eaten, he sat back, relaxed, and enjoyed a glass of hot tea. Then he went home—on foot.

I felt something close to envy. When was the last time I ate at a café without taking photos or watching videos? While just enjoying things? I was struck that he had walked to and from here.

I promised myself I would look after my body, eat healthy and keep active. It would be all the more important to do those things if I didn’t end up having a family and continued to live alone—health is an investment. I guess that when you’re alone, thoughts like these appear like mushrooms in the rainy season, but still.

When I left Kafetien 88 a little later, I found myself noticing how old the surrounding buildings were. Supposedly, before my great-grandfather moved to Bendul Merisi in southern Surabaya in the 1940s, he lived in this area. I walked past structures with paint peeling and mould on their walls, electronic shops, a Confucian temple, a massage parlor, a local office of the political party PDI-P, a Chinese Buddhist temple, old tattered hotels, a satay stall, a soto stall, and a cigarette shop owned by a Chinese-Indonesian man that sells Djisamsoe Premium for 20,000 rupiah, $1.50. This area didn’t feel foreign to me anymore. And because I was alone, I had extra time and inclination to pay attention to all of this around me.

Then there were old houses, occupied mostly by Chinese-Indonesians. They tended to have white walls and iron trellises across their doors and windows, well-painted fences and ornamental plants on the terraces. I thought about the minimalism and elegance of these houses. No needless complexity: easier to look after.

Because there’s no musholla in Kafetien 88, that day I performed the Maghrib prayer at a musholla in a nearby alley. Motorbikes and becak cycle rickshaws were parked at the alley’s entrance. Young kids were singing praise to Allah and the Prophet from the musholla speakers. Sandals were scattered around the entrance gate. I washed my face with the ablution water. A member of the congregation offered me a mukena in Javanese with a thick Madurese accent. Life went on, ceaselessly busy, each person going at their own pace, and in their own direction.

Amid all these old structures on Jagalan Street, I thought about how I was still reasonably young – perhaps too young to be drowning in sadness. I thought: if I die from the pandemic, will I do so whilst depressed? Night had now fallen and the streets had grown quiet, the reverse of conditions here during the day. I got on my Honda Beat scooter and drove it slowly.

I guess this is how it feels to be one of the girls in Wong Kar Wai’s films: puffs of cigarette smoke, heritage buildings, dim neon lights, and in the middle of a city both frenetic and neglected, ambitions blurring amid smoke and dust.

*

After almost a year, I got a new boyfriend. I’ve started going to Kafetien 88 with him.

Recently, I’ve begun ordering differently: nasi timbel with anchovies and a sour tamarind vegetable soup on the side, a glass of iced tea, plus kaya toast. Trying new foods I see as a way to signal the beginning of a new phase of my life.

After the overcast weather in my thoughts gradually dispersed, I started doing lots of activities. I started painting again and listening to music. I also began eating fruit and vegetables every day, sleeping a lot, and smoking less.

Maybe in the future sadness and loneliness will come again. Maybe at some point I’ll again watch Chungking Express in a spill of tears.

Or, maybe my attitude will be different, and I’ll decide that life doesn’t have to be as sorrowful as all that. Maybe I’ll realize faster in future that there’s always hope to be found in some narrow laneway in this city, and in other cities.

Recently, I re-considered something. Maybe the clouds of smoke around Tony Leung in In the Mood for Love—which I had always thought of as a representation of his anxious preoccupation—actually just came from a mosquito coil under the table.

© Vema Novitasari

English translation © Lise Isles