Want to Bike Ride the Indonesian City? Prepare for Challenges

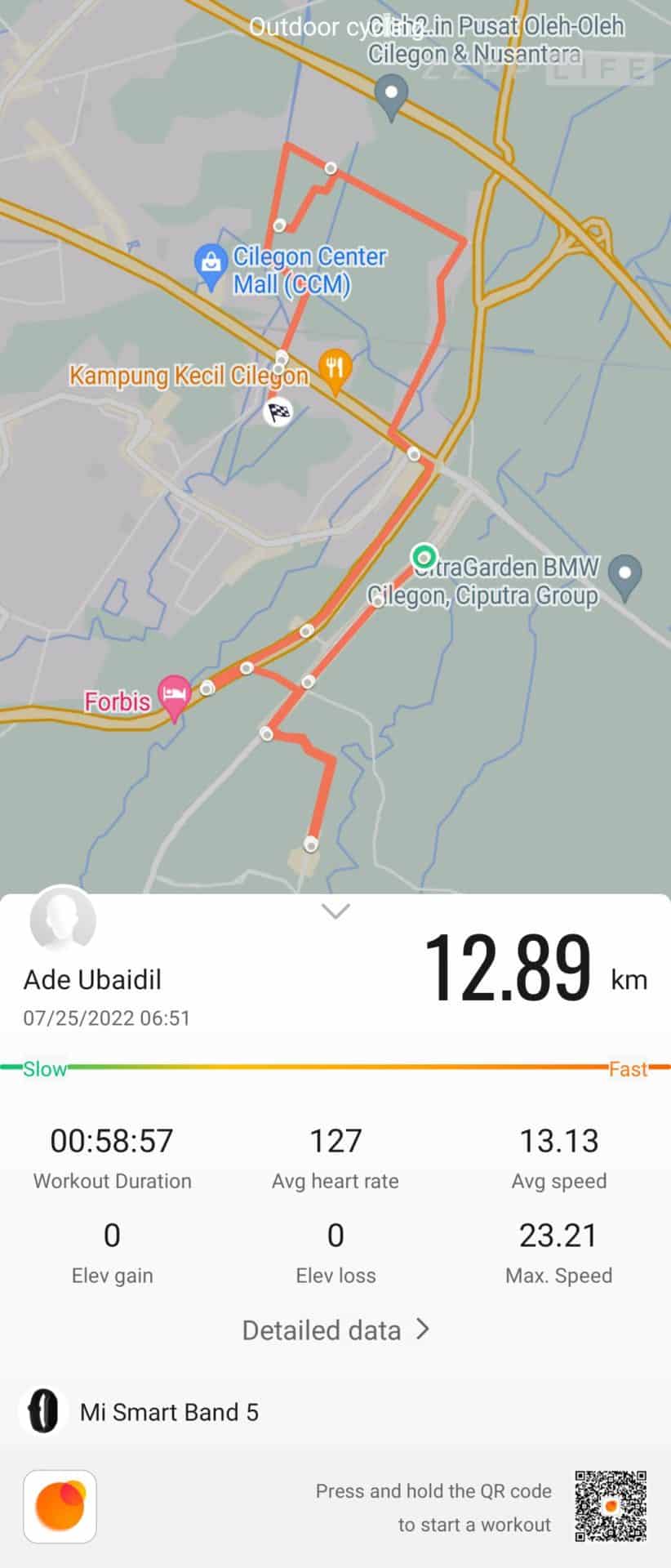

Photo: Ade Ubaidil.

A bike-seat | 2,500 words | Translated from Bahasa Indonesia by Dan Benjamin

Some time ago, the journal Nature published findings from scientists at Stanford University about the countries of the world whose people most dislike walking. Occupying first place was the nation of Indonesia.

I wasn’t surprised to read it. I’m one of those people.

The article went on trace the reasons why Indonesians, typically, can’t be bothered walking. The heat was put forward as a reason, as was inadequate infrastructure. I’d be more inclined to argue that walking is just not part of our culture. Different to say Japan or Hong Kong, where people are educated from an early age to get used to walking from place to place.

I’ve just started to get into bike-riding, though. An alternative to walking which still involves moving your body. Bike-riding is something I’ve wanted to try for quite a while, for one reason only: doing it can make my body healthier and my life longer. Although longevity is ultimately in the hands of God, bike-riding is one way I can endeavour to bring it about.

In the last few years – especially since the pandemic – many people in Indonesia have likewise been touched by bike-riding fever, likewise coming to realise the importance of living healthily, boosting their immune systems, plus seeking out new interests and hobbies. Not only regular people, but celebrities, public figures, even high government officials have joined in to create a buzz around bike-riding and campaign for its widespread adoption. Another positive is that a culture of bike-riding can aid our transport woes, being a way to reduce the traffic jams and air pollution caused by motorbikes and cars.

I was born and raised in a city on the western-coast end of the island of Java, looking out onto the Sunda Strait. Cilegon is an industrial city. We’re sometimes dubbed the city of steel, as we’re the biggest steel producer in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, facilities for bike-riding here are far from decent. The city’s spatial layout is also far from beautiful, though the government is attempting to improve things. If we compare this city to, for example, South Tangerang, about 80 kilometres from Cilegon and on the outskirts of Jakarta, it’s quite a difference.

My decision to buy a bike this year was also prompted by moving into a new house, just-renovated. I was imagining that, every time I’d go between my parents’ house and my own, I could pedal a bike. It wouldn’t take too much time, I figured, given they’re only around five kilometres apart.

Great projections began to play in my head. I dreamed, after I had already become a pro at bike-riding, of making a trip to Serang by bike. Usually that takes about 30 minutes: I was already curious how long I would need. And because Cilegon isn’t all that big, it’s possible to ride around its perimeter in a day – I’ve seen an Instagram Story of my friend, who often rides over 100 kilometres a day, doing it. Crazy!

On day one, I was full of beans. When the bike I’d ordered from Facebook Marketplace arrived in the afternoon as a packet on my doorstep – yes, I bought my bike online – I hurriedly got in touch with my nephew to help me assemble it: he knows bikes well, and I didn’t have the right tools. Ega said he had free time after work.

‘What time do you get home?’ I typed into WhatsApp.

‘I should get back around the Maghrib prayer’, he replied.

Is it just me who feels that, when waiting attentively for something to happen, time goes slower? I only had to wait three hours, but it felt like ten. At eight o’clock, I went to Ega’s house with my 14 kilogram bike. Supposedly, compared to most bikes, the bike I’d bought is light – I’d chosen a United Fixie Slick 700 hybrid, a classic model, different to the bikes that are all the rage now, easy to take on asphalt roads but also on dirt tracks in the mountains. Still, it was lucky mine and Ega’s places are only a stone’s throw from each other.

Soon my bike looked just like the pictures – though there were some leftover ring pedals, and a promised extra back light was nowhere to be seen. But I had signed up for such things, hadn’t I – that’s how it goes when ordering online. Then a new problem appeared. The shifter we had just installed didn’t function right. Every time I tried to shift gears, I couldn’t.

‘There’s no chck-chck sound’, Ega observed, mimicking the sound a working shifter is supposed to make.

‘There’s always something, hey’, I said, confused. I am well and truly a layperson when it comes to this stuff. ‘So what now?’

‘You could try to ask for a replacement from the seller. Or you could just take it to the repair shop in Jombang Kali.’

I decided that I would go for the second option.

The last time I had a pushbike was in elementary school, just after I was circumcised: a bike was bought by my parents using money contributed by friends and neighbours who came to visit and pray for my recovery. Since that time I’ve rarely, almost never, ridden a bike again. Especially after I learnt how to drive a motorbike when in middle school. After that I used a motorbike to go everywhere.

Based on data from the Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2020 there were 136 million motorbikes in Indonesia, including 81 million in Java. Pushbikes are very far below those numbers. Motorbikes give you comfort on the road, and you don’t need to go to all that trouble of pedalling. To only turn on the machine then gas it, all for a more-and-more affordable price, often obtained via credit and monthly instalments… my historic reasons to choose a motorbike indeed made perfect sense.

Next morning I was up very early. But not as normal. Usually, after the Fajr dawn prayer I go back to sleep. But not today. I’d already cleaned myself up and dressed. Now I wheeled out Black Slebew – my interim nickname for my bike. I bid my housemates farewell and went off to ride by myself.

The first thing I felt when on top of that bike was a feeling of uncomfortableness from sitting on the seat, which was slim. It may reasonably be said that my ass is on the large side, and thus requires a level of support that is also on the large side – one day in future, it seemed, I would get this bike-seat replaced. Perhaps I’d found another reason why most people are happier on a motorbike.

On starting to ride, I was a little nervous. The seat was also set too high. I almost fell, unable to find my balance. On top of everything the gears couldn’t be shifted: it was really truly far from comfortable. I resolved to swiftly get the bike fixed.

Because I was on a bike I chose to take a backroad, the type of road I rarely take if I’m driving a motorbike or car. Although the road was full of holes here there and everywhere, still I chose it. The morning was filling with self-torture. I had to stop often on this road to wait for pedestrians who were taking their children to school. On backroads, as opposed to main roads, if you’re a bike-rider – or using any vehicle, actually – pedestrians will airily go about their business with no inclination to let you pass. Moreover this road was often obstructed by vendors selling breakfast. It was becoming a disorderly morning.

At 6:30, I paused in front of a vendor selling bubur ayam, hot chicken porridge. My smartwatch, integrated with my phone, informed me I had ridden just over two kilometres. A good number, I thought, for a beginner. I took a minute to appreciate myself. Then, because my breath had started to get heavy and unruly, I decided to fill my empty stomach with a bubur ayam breakfast here at this stall, which was already getting busy.

I had problems parking my bike. One, there wasn’t really a place, as the bubur stall stood immediately in front of the asphalt terrace of a shophouse that was closed, with all vacant spots taken by motorbikes. Two, my bike didn’t have a kickstand. I started to look for a pole or wall to lean the bike on. I became aware that people were watching me closely, especially the bubur vendor: I saw him observing me and my bike very attentively indeed. Finally, I leaned the bike on one of the pillars holding up the roof of the front part of the shophouse.

‘I’ll take one, Mas. No spring onion’, I said briskly.

‘Okay, Mas’, the vendor said, politely. He poured some warm tea into a small glass, then held it out to me. While waiting for my order I sat on a small wooden bench, about a meter long. I searched on GoogleMaps for the address of Herman Bike, the shop my nephew had recommended. There it was. A phone number was listed. I hurriedly rang it.

I was still trying to bring my breath under control, huffing and puffing, but I managed to enquire and find out that they opened at 7.30am. One more hour, I thought.

My bubur ayam arrived. I devoured it quickly and without so much as a word. It’s tiring, it turns out, pedalling a bike with the gear constantly stuck in four. Even though I had imagined riding a light bike. On the other hand, the bubur ayam felt more enjoyable to eat this morning, I guess because I was in such exhausted condition.

At 7am, I started to pedal again. 30 minutes was enough time to get to the repair shop, I thought. It was about 2.5 kilometres away. Sounds close, but actually, the route was a tough one for a bike-rider, lots of hilly sloping ground, lots of pot-holed rough stretches, lots of winding and twisting. But that’s how it is on our backroads.

I turned my smartwatch back on. I thought about which road would be best to tackle on a bike, the least steep. My legs were starting to feel sore, especially in the thighs and knees. My skin was feeling like it had been pulled and stretched to its maximum limit – painful. But I was convinced all this was just a transitory effect, the kind of thing beginners feel when they try anything new.

Other things that differentiate backroads from main roads here are: the backroads don’t have traffic police, the people using them are only people who live close by, and they’re missing the large trucks and buses that take the main roads to Merak harbour at Cilegon’s far end. Yet these backroads connect lots of kampung neighbourhoods all throughout the city, as long as you’ve memorized the twisting winding routes.

Every time you take an older-style road like this, your memories will take you back into the past, to your childhood, which was beautiful, with meaningful problems yet to appear.

Travelling this route, it seemed to me that I was seeing again many things about my city which had long disappeared from my field of vision. When I’m driving a scooter or car, my focus is only on the straight section of road in front of me. But when on a bike, especially on these backroads, I came to see in much more detail homes, new buildings, sports ovals, and the transformation of land, with areas I recalled as being full of old houses now torn down. Often, it can feel like time passes by us very fast. On a bike, everything started to feel slower for me.

It seemed like there were more and more people everywhere, backroads that had always allowed untroubled travel now had traffic jams, and what had in the past been essentially villages were filling with housing complexes and industrial supplies warehouses. The city had extended itself even into far-flung kampung corners, that had once been lovely but were now losing that quality. Long ago, I recalled, when still in school, my friends and I had often spent time on this backroad. The asphalt street surface wasn’t yet so wide, and there were still lots of dirt-paths all around, and fields full of long grass, and kids playing football. Now all that’s getting hard to find. If you want to play football now, you need to rent one of those huge indoor arenas.

Actually, I don’t especially agree with developers wanting to build housing estates in this sort of kampung area. In a big city we should guard a few nice spots, at least, so that they stay as before. But, as always, the changes of the era cannot be stopped. Change is the only constant in life.

Instantly, my mood had changed. With my Bluetooth earbuds in, I played the mellow song ‘Wish’ by Choi Yu Ree, that’s been lifted for the soundtrack of the Korean drama Hometown Cha-Cha-Cha that’s airing on Netflix.

The most basic thing I learnt that morning was that one way for us to ensure we enjoy riding a bike is to guard our mood. Because a bike is an extension of our own bodies. It’s different to driving a car or motorbike: when our moods are bad, the car or motorbike will still work as normal. But on a pushbike, it depends on how we’re feeling: stable or unstable, good or ugly, hurried or relaxed. Weather likewise influences your emotions and thus your performance: your body getting more and more sticky with sweat, and the heat of the sun getting more intense can make you lose focus. The rub is, the better your mood, the better you ride your bike. But if your mood is unsettled, one kilometre on a bike can feel a long way indeed.

And that was what happened because of my indeterminate inner state that morning. I had imagined my bike would come in prime condition, but on the first day, I was going to the shop to get it fixed. I felt an annoyance, but what can you do.

Finally, I chose to pull over for a bit, and permitted myself to look around. It seemed my body needed a long rest. I let my eyes take in some houses lined up unevenly, and a bunch of vehicle drivers brawling and having a horn-honking contest.

I glanced at the smartwatch on my wrist, which showed it was now already 7:30, although it was still a long way to the repair shop. My estimates had really been awry that morning.

But I can guarantee: by the time you all read this essay, I will be a total pro as a bike-rider.

© Ade Ubaidil

English translation © Dan Benjamin.